The argument goes that strikeouts require more pitches than outs on balls in play. After all, your fielders can convert an out for you on only one pitch, while a strikeout demands a minimum of 3. This argument is most often extended anecdotally to young pitchers who have yet to "learn to pitch" and, because of their inexperience, ego, stupidity, or any combination thereof, take themselves out of games early by running up their pitch counts chasing strikeouts when they should be inviting the batter to hit the ball.

This seems to make a lot of sense. So too, however, did the general notion that good pitchers as a rule were better at inducing outs on balls in play, so perhaps we better check into this theory as well. As it turns out, the two theories are somewhat linked. The assumption that contact plate appearances are better for pitch counts than strikeouts is heavily dependent on the rate at which outs are converted on contact plate appearances. If you can get a hitter to put the ball in play on one pitch, that's great, but if it takes 3 balls in play to record 1 out, then you might as well have just struck the guy out.

Obviously, it does not usually take 3 balls in play to get 1 out, but neither does it usually take 1 pitch to induce a ball in play. The question is, can contact be induced in few enough pitches to offset the number of balls in play it takes to record an out? We are concerning ourselves with pitches per out because the issue with pitch counts is how deep into the game a pitcher can go, and we measure that quantity in innings, or, in other words, in outs. Therefore, the primary concern is how efficiently a pitcher uses his pitches to record outs. This question is central to the issue of how strikeouts and contact PAs affect pitch counts, yet it is largely ignored or taken for granted. The answer is yes, it is more efficient to get outs by inducing contact, but just barely.

Since 2000, pitchers have used .15 more pitches per out to get strikeouts than to get an out on a ball put in play. In recent years, the gap is even smaller (about .10 over the past few years). The reason the difference is so close is that the number of balls in play required to convert an out, on average, very nearly offsets the drop in pitches required to induce contact versus striking a batter out.

Over the span considered, the league BABIP is just under .300. However, that figure excludes home runs for the simple reason that they are dealt with separately for most purposes: since we are only concerned with the conversion-rate of outs once the ball hits the bat, we have no reason to exclude HR, and the rate at which hits are recorded once the ball is hit rises to .325. This also excludes the error rate, which further reduces the probability an out is converted on a ball once it is hit. Of course, we must also add in the possibility for the double play, since 2 outs on one pitch are more efficient than just 1. Considered all together, these factors are just enough that it doesn't make much difference in your pitch count if you strike out more batters or get more outs on balls in play.

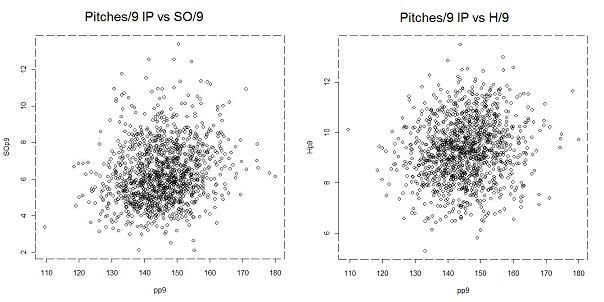

To illustrate this point, the following graphs show every pitching season since 2000 with at least 100 IP measuring the pitcher's pitches thrown/9 IP against his K/9 rate and against his H/9 rate. Keep in mind that since most pitchers allow very close to the league average BABIP over significant samples, hit rates are largely dependent on the rate of balls in play a pitcher allows, so we're basically looking at how pitch counts relate to high contact pitchers and to low contact pitchers:

As our data suggests, there is no emerging pattern that either high strikeout pitchers or high contact pitchers require more pitches to get through 9 innings. For the most part, it doesn't matter how frequently a Major League pitcher strikes out hitters or how frequently he allows hits as to how many pitches he has to throw. The trade offs of one compared to the other mostly cancel out.

What, then, is the primary determinant in a pitcher's pitch count? It's walks, of course. They are the one event that costs pitches with no chance of an out, and it shows. Look at the graph comparing pitchers' pitches/9 IP to their BB rates:

Now here is a clear pattern. Simply put, by far the strongest factor in how many pitches a pitcher needs to get through an inning is how frequently he walks batters. Almost every time you hear a broadcaster or analyst talk about how a pitcher throws too many pitches because he strikes out too many hitters, the real reason will be because the pitcher walks too many hitters, not that he strikes out too many (unless, of course, the personality has not checked the facts and is commenting on a pitcher who doesn't even throw more pitches per inning than normal). That's why pitchers like Roy Halladay, CC Sabathia, Cole Hamels, Johan Santana, Josh Beckett, Rickey Nolasco, and even Tim Lincecum were all taking fewer pitches than average to complete each inning in 2008 and pitchers like Barry Zito, Tom Gorzelanny, and Miguel Batista were all taking more pitches than average. It has nothing to do with the strikeouts. It's the walks.

Of course, there is some relationship between walks and strikeouts, but not enough that you can look at a pitcher's K-rate and tell all that much about his walk rate. The correlation of a pitcher's walk rate and K-rate is actually very weak-less than .1, which means if you know a pitcher's K-rate, you only really have about 10% of the information needed to estimate his BB-rate. An individual pitcher's K- and BB-rates will generally rise and fall together, but how those rates relate to each other varies widely from pitcher to pitcher. So while a pitcher with poor control may find it more effecient to cut down on his walks at the potential expense of some of his strikeouts, the strikeouts are really not the culprit, and a pitcher who already has good control has no reason to cut down on his strikeouts purely to reduce his pitch count, as he generally won't see any noticeable results.

Continue Reading...